I stood up from my seat in the pew, ready to carry a heavy weight. Could I take a punch? I guess this was as good a time as any to find out. Only it would have to be a wet one, like a kiss, because it was starting to rain.

***

When someone dies, you still need to do the normal things. Like shave, make sure your shirt is wrinkle-free, help your kids get ready for the events of the day. There’s fixing up the daughter’s hair, helping the son with his tie, and you eat a little bit if you’re hungry or you know you’ve been forgetting. Then there are the abnormal things, the new things. Trying to find a way to comfort your mother, who’s just lost her Father. Remembering the last time you saw someone, how they looked. How they looked compared to what you remember them as.

The first time we found out my Grandfather had cancer, we quickly gathered plans to race down and see him. It always amazes me how our small family can create chaos out of quiet, when given the sliver of a chance. This was more than a sliver. It was just after Easter, the time of year that Connecticut is in the full bloom of spring while northern New England is still going rounds with winter, hoping at best for a draw. We escaped the dirty snow banks to flowers on the trees and something like blue in the skies. We were told, rightly or wrongly, that we needed to visit Grandpa because things did not look good. The kids ran around the back yard, we setup lawn chairs, the aunts and uncles gathered. You talk about work when you don’t want to talk about the future.

Four years later, he died. Four years of ups and downs, long nights we could only imagine with all the distance of 300 miles and a half a climate between us and my grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins and friends and neighbors. What did my mother go through in those four years that I could learn from? Not just the fear of driving to the hospital, but the loneliness of driving home, to go to bed, to wake up and go on with their lives the next day, waiting for news.

What about my Grandfather, at the center of it? You’ll need to change your eating habits, try to like new things, have patience forced on you like an icy sidewalk when you fall. The patience of waiting rooms, test results, the patience of waiting to see if a new treatment works or what else it will do to you while you’re trying to battle the larger of two evils.

When I think about those four years, I imagine the patience is tempered by the vast uncertainty of length, like how driving somewhere the first time always seems so long. Do you lose sense of time wondering if today will be a good day, or if this month will bring setbacks, or this season will be filled with promise as the enemy retreats? And come to think of it, did the enemy retreat, or are they regrouping? When you’re a child, time alternates between enemy and friend at different times. Growing up means understanding time, befriending it, ultimately controlling it. The cancer takes that, returns days to weeks, hours to months, removes your ability to predict and balance your present with your future.

Secretly, I didn’t think he’d get well, only manage, with bouts of triumph and resolve, while a steady decline walked on, ignoring his will.

***

He died in February, yet another time of year when Maine is consumed by the darkness and the whiteness of winter, while Connecticut turns the corner. There weren’t quite flowering trees, but the snow had given way to rain and the immeasurable dark skies were now just gray, with a hint of blue.

We were ready. I had a haircut and bought a larger wedding band to fit over my broken finger. My family would immediately notice if I wasn’t wearing a ring, and even a swollen and purple knuckle would not excuse the adoscelent arrogance of not wearing it to such an occasion. Death is one of the reasons we maintain traditions in the first place.

Saturday morning, we were groups of dark suits and dresses, piling into dark cars under deep gray skies. They weren’t showing clear signs of lightening; that took the promise out of our small talk about the weather. Some of those gathered were handed umbrellas by the funeral attendants, until the umbrellas ran out. My own children had never been to a funeral; never seen my wife and I at our most vulnerable. We would need to expose them to the power of grief and still hold them close enough to not feel alone.

A traditional Catholic mass anchored the solemnity. Even for those people who grew up outside of the church, it provided meaning to our dress and united our quiet solitude. The sermon reminded us that my Grandfather received comfort as dramatically and as surely in the other world as he had been plagued by pain and decline in ours. This peace was possible in his new place because, the priest assured us, “Only the father knows the son,” and “only the son knows the father.” This was religious in intent. Then my uncle got up to deliver the eulogy for his father, gone after a lifetime, and those words meant something even more to me.

***

After a short drive from the church, we gathered at the gravesite. The rain clacked on umbrellas above us, and below the somber quiet followed us from the church. They’d erected a canopy over the grave for the service. My grandmother and aunts and uncles and friends gathered in seats for the military ceremony, honoring my Grandfather’s service in Korea. I stood outside the canopy, listening.

Approaching middle age, I realized I had been wondering, for nearly 30 years, how my Grandfather felt on the long boat ride from Korea back to the United States. I know from stories that he and his friends played cards to relax and pass the time, but what else? What mix of confidence and relief showed itself on the faces and in the words of him and the men next to him? Did he dwell much on the choices that lay before him, as impossibly wide as the ocean? Did he plan out the universe he would co-create, that now stood gathered around him in the cold and wet world he left? You rarely think of something when you’re in the middle of it, even as long as a life.

My wife pulled my daughter closer under her umbrella. Men in uniform moved through traditions. My Grandfather had never been as far away from that boat and its possibilities. No harm could come to him anymore as he stood with the Father, in rest following a lifetime of choices and sentences, lucky and smart, fair and cruel.

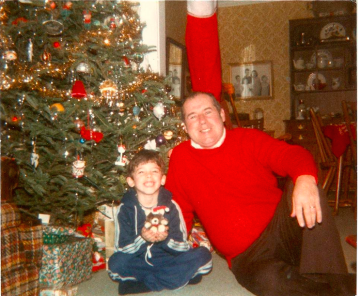

My son looked up at me, and I looked back at him. I don’t think you learn how to act at funerals, any more than you learn how to control life. You befriend time, and you carry an umbrella, and when you escape one battlefield, you take a moment to laugh and play cards and maybe you catch a glimpse of the next adventure you’ll have a hand in creating. Then you go towards it, with fear and confidence, invincibility and fragility. Peace and loss.

As my son stared at me standing in the rain, his face moved for a second. I think it was recognition. Then he lifted up his umbrella, stretching to the limits of his reach to place it over my head. I took it from him and held it over both of us. We were out of the rain for the time being, but it was still loud as hell and inches above our heads. He stood close to me to keep out of the cold.

Only the father knows the son, and only the son knows the father.

Leave a Reply